My father-in-law, then a trainer at General Motors, was fond of telling the “frog story” to illustrate the notion of ‘Situational Awareness’. The gist of the story is that a frog will jump out if placed in a pot of hot water, but if placed in a container of slowly heating water will eventually be boiled to death. The moral of the story was that we often fail to become aware of critical changes in our environment when those changes occur perceptibly slowly.

Situational awareness refers to the ability to understand and interpret surroundings, recognizing potential dangers, and anticipating future events. The behaviors associated with Situational awareness have been extant for centuries, but the designation and the academic discussion of it is of recent vintage. The phrase was introduced by Endsley in a seminal paper published in 1995. Since that time the concept has been used in the analysis and the teaching of wide swaths of human undertakings. Situational awareness is the designation given to a form of mindfulness (cf: Zen mindfulness), which holds in one’s mind a map of the entire environment a person may encounter.

It is thus to be distinguished and stands nearly opposite the ability the ability to focus on a specific narrow problem, whether it be scientific, social, political, or theological. This ability to focus is essential for the thinker and for specific problem-solving. However, it is different from the situational awareness required of the practical man or woman. Situational awareness is akin to what Aristotle termed phronesis, translated usually as “practical wisdom”.

Formal training in situational awareness has become essential for several disciplines. Cybersecurity and law enforcement, flight training, and medical disciplines, such as anesthesiology and emergency medicine, all involve situational awareness training. Perhaps the quintessential example of the application of situational awareness is the air traffic controller, a function all too much on our minds of late. Likewise, the “rear guard” in military sorties functions to make the team situationally aware.

The changes in the culture and structure of the western world, while largely imperceptible, are never-the-less profound and have already dramatically affected higher education. Popular interest in higher education has lessened. The number of people of college-going age that want to go to college has decreased. Government support has wavered, often dramatically. Almost four hundred and seventy institutions of higher education have disappeared (either closed or merged) between July 2004 and June 2020, most of these actions driven by financial exigency. However, notably many college or university chief executives and their teams, and governing boards and their members have failed to notice that the proverbial water is heating up quickly and to critical levels.

It might reasonably be argued that higher education leaders have been set up for failure, particularly college and university presidents or chancellors. These deeply committed leaders are selected by a process which increases the likelihood of failure at situational awareness. They frequently emerge from a lifelong commitment to a specific discipline, often a narrow discipline or problem – which requires the very kind of focus which is inimical to the adequate development and exercise of situational awareness.

Most universities use the traditional ‘search committee’ process for identifying candidates for president or chancellor roles. Such committees are invariably heavily populated with faculty and alumni who, in turn, have often contributed much to improving the human condition by focusing successfully on a narrow field of study. But they are often devoid of significant situational awareness and its value, particularly as it pertains to the broader and complex environment in which higher education is currently sitting.

The chief executive search process was designed or has evolved (perhaps inadvertently) to reproduce itself and its leaders. And it does just that. The successful candidates are often contemplative and eschew actions based on summary judgement. They are risk adverse by nature. They would rather be late than wrong. These are wonderful traits in the right context but unlikely to promote the development of the kind of broad-based situational awareness so critically needed in higher education today.

Today’s higher education leaders often fail to notice that the water in which the sector and their institution sits is slowly heating to crescendo. Sometimes, because they choose not to grasp the major trends their institution and their sector are facing, but most often, because they simply are not focused nor trained to secure and use broad-based situational awareness. Leveraging external parties can be of great help in better understanding the institution’s environment and state, yielding valuable situational awareness insights. Let SPH assist your leaders in obtaining and leveraging critical situation awareness insights.

To learn more about SPH Consulting Group and how we can help your organization, contact office@sphconsultinggroup.com.

Writer: Lloyd Jacobs, Senior Consultant, SPH Consulting Group

© SPH Consulting Group 2025

I am the daughter of an exceptionally good high school athlete. Of all the genes that were passed down from my father, I got none of the athletic ones. Even though I could not play, I loved to watch sports with him. I particularly loved college basketball and March Madness. As a student of the game, I have consistently been captivated by the performance of point guards like Magic Johnson and Stephen Curry.

The point guard isn’t necessarily the tallest player, and often not the most prolific scorer. But they understand the game plan, have a wide array of skills, and can make smart adjustments in the moment. They can simultaneously communicate with the sidelines and focus down the floor. Once everything is set, they put the ball in motion and, if they have done their job well, good things happen. If the strategy gets bogged down, they reset their teammates or fill a gap themselves.

I have served as a chief of staff to five different presidents, each facing vastly different challenges. I think I loved the role because the chief of staff to a president or chancellor is the administrative equivalent of the point guard. They help the institution’s executive execute their strategy and assist the cabinet in getting to the right positions to fulfill their role.

In a partnership or merger discussion, this role is essential. The institution’s chief executive now must not only take care of the regular day-to-day business of running the university, but they must also take on the additional burdens of designing a massive organizational change. An already daunting job just got even more complex.

The chief of staff is an essential partner in ensuring that the president or chancellor can balance the urgent daily demands with the important task of planning for the future. These servant leaders must:

- Ruthlessly prioritize the chief executive’s time to ensure that this scarce resource is focused on things that only the they can do.

- Ensure strong communication flow between all important constituencies and the chief executive. It is far too easy to fall into the trap of only listening to the loudest voices.

- Monitor relationships with key constituents to ensure that the chief executive has the pulse of their constituents, and that the right people are engaged at the right moment.

- Ensure consistency in chief executive communication. What is communicated about the current state of the institution must be consistent with where the institution is likely going. Inconsistencies in communication create confusion and mistrust.

- Consider the human side of leadership. In challenging times, when the work is hard, the chief of staff can help everyone who is “heads down” to remember that the work they are doing is for the ultimate benefit of their students and their community. The chief of staff aims to help the entire team continue to find the joy in and remember the purpose of what they are doing.

The chief of staff is a critical extension of the chief executive in many circumstances, but especially during the consideration, planning, or execution phases of any major institutional restructuring initiative, such as a merger or acquisition. And they serve as an important connector to the rest of the executive team.

I’ll close with a quote from the GOAT himself. When once asked about the point guard role, Magic Johnson paraphrased a line from one of the greatest speeches of all time… “Ask not what your teammates can do for you. Ask what you can do for your teammates.”

To learn more about SPH Consulting Group and how we can help your organization, contact office@sphconsultinggroup.com.

Writer: Karla Leeper, Ph.D., Consultant, SPH Consulting Group

© SPH Consulting Group 2025

Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) have long stood as beacons of educational excellence, cultural preservation, and community empowerment for Black students in the United States. These institutions have consistently prepared underrepresented students for impactful societal roles. However, political obstacles and historical underfunding, largely driven by racial disparities, have posed persistent challenges to their progress.

In today’s higher education landscape, HBCUs face increasing pressures due to declining enrollments, limited funding, and rising competition from predominantly white institutions (PWIs) and other minority-serving schools. Given this environment, strategic partnerships and mergers may provide valuable opportunities for sustainability, resource expansion, and mission reinforcement.

A Brief History of HBCUs

HBCUs were established in the mid-19th century to offer higher education opportunities to Black Americans, who were largely excluded from most colleges at the time. Cheyney University, founded in 1837, was the first HBCU, followed by institutions such as Lincoln University in 1854 and Howard University in 1867. These colleges played an essential role in developing Black professionals, fostering leadership, and enabling upward mobility.

During the Reconstruction Era and much of the 20th century, HBCUs served as the primary institutions of higher learning for Black students. Their significance was further solidified during the Civil Rights Movement. However, desegregation introduced new challenges, as Black students began to attend PWIs in greater numbers.

The 2023 Supreme Court decision to end race-based affirmative action in college admissions has led to increased enrollments at HBCUs. This rise reflects a renewed interest in inclusive educational environments. Despite these changes, HBCUs remain vital in nurturing student identity and providing leadership in advancing social justice and equity.

Challenges Facing HBCUs Today

HBCUs continue to navigate significant challenges, including:

Financial Instability: Historically, HBCUs have endured underfunding due to racial politics and limited governmental support. These financial limitations hinder their ability to modernize infrastructure, invest in technology, expand academic offerings, and compete for highly qualified faculty by offering competitive salaries.

Enrollment Challenges: In the past HBCUs faced declining enrollments, for a myriad of reasons. However, due to changes in society and the 2023 decision by the Supreme Court the challenge has shifted from decreased enrollments, to HBCUs not having the capacity to serve the current interest of Black students who want to attend an HBCU.

Political and Social Pressures: HBCUs must also contend with policies and societal issues, such as systemic racism and economic disparities, which add layers of complexity to their operations and missions.

The Role of Partnerships for HBCUs

Strategic partnerships can offer HBCUs a means to expand academic programs, secure additional funding, and improve student opportunities. Collaborations between HBCUs, PWIs, corporations, and research entities bring several benefits:

Academic Growth: Partnerships with external organizations can introduce new programs and disciplines, such as Benedict College’s collaboration with Rize Education to add Neuroscience, Digital Marketing, and Supply Chain Management programs.

Enhanced Resources: Partnerships often result in increased funding from philanthropic organizations, businesses, and government agencies, which can be used to modernize facilities, support faculty, and provide scholarships.

Student Enrichment: Joint initiatives facilitate internships, study-abroad programs, and career placements, enriching student experiences and future employment prospects.

Knowledge Exchange: Collaborations enable HBCUs and their partners to share best practices in pedagogy, technology, and administration, driving innovation and institutional growth. For example, partnerships with tech giants like Google and IBM have enabled HBCUs to strengthen STEM programs and prepare students for high-demand careers.

HBCUs and Mergers: A Double-Edged Sword

While mergers can enhance financial stability and operational efficiency, they pose risks to the distinct identities and missions of HBCUs. Preserving these unique histories is critical, as HBCUs have played a key role in advancing educational equity and economic opportunity for Black communities.

One successful example of a merger is the formation of Clark Atlanta University in 1988, which combined the strengths of Clark College and Atlanta University while preserving their individual legacies.

For mergers to succeed, equitable resource allocation is essential. Transparent communication with alumni, students, and community stakeholders is also necessary to build trust and ensure a smooth transition.

HBCUs: A Path Forward

Strategic partnerships and mergers, when approached thoughtfully, present promising solutions for HBCUs to overcome contemporary challenges. These strategies can provide access to much-needed resources, foster innovation, and open new opportunities for students and faculty alike.

To succeed, such initiatives must respect the rich heritage and core values of HBCUs, which have defined their legacy of educational excellence for over a century. By embracing these pathways, HBCUs can not only sustain themselves but thrive, continuing to play a crucial role in shaping the future of higher education and society.

To learn more about SPH Consulting Group and how we can help your organization, contact office@sphconsultinggroup.com.

Writer: George Bradley, Ph.D., Advisor, SPH Consulting Group

© SPH Consulting Group 2025

With the fall semester now underway and enrollment census complete, some colleges are facing the stark reality that net tuition revenue will fall short of budget expectations. While some institutions will adjust and reforecast their revenue expectations, others will be left wondering if there is enough cash to get the institution through the fall semester and the academic year.

Responsible leadership requires chief executives (i.e., college or university presidents or chancellors) and chief financial officers (CFOs) to take a hard look at the institution’s liquidity and cash reserves needed to meet expenses and fulfill the institution’s mission. It is the latter that is the most essential to meet. We, as leaders, must ensure that the institution has sufficient cash to meet its academic and co-curricular requirements. Too often, leaders of financially challenged institutions make survival decisions without fully understanding or even considering how those decisions impact the institution’s mission. Cutting budgets to survive is essential, but leaders must also ensure that these decisions also can create a thriving, mission-driven experience for their faculty, staff, students and alumni. Surviving is not the same as thriving.

Chief executives and CFOs must take account their cash and cashflow and map out their obligations for not only the current fiscal year, but the summer months that lie ahead as well. As we all know, colleges and universities typically have two key tuition revenue months within the calendar year – August/September and December/January. Beyond these key periods, understanding the burn rate of the institution (i.e., how much cash does the institution need monthly to fulfill its financial obligations) is important. However, we should not forget the financial needs of the following summer, as institutions need to meet payroll and other expenses before the next round of fall revenue becomes available. In developing a cashflow model, it is prudent to realistically plan out for at least the next 18 months, if not for at least the next three years. There should be no optimism in your cash model – the institution simply cannot afford it.

The realization of a realistic cash position requires several strategies beyond the cashflow model and budget forecast. It may also be time to make any necessary reductions in cost, aiming to minimize the impact on the mission and/or the student experience. Frank conversations with the Board of Trustees, banking partners, lenders, and campus affiliates will be necessary. Campus affiliates, such as those providing dining and residence halls, will need assurance that you will pay your obligations in a timely manner – if not, this is also the time to navigate a payment plan that works for both the institution and affiliate.

The most challenging of these conversations is with the Board of Trustees. As trustees, they have a fiduciary responsibility that extends beyond the Board room. This fiduciary responsibility requires each trustee to fully understand the financial challenges that are confronting the institution. As chief executives and CFOs contemplate how best to inform the Board, there are three essential steps in the conversation:

- Honesty

- Transparency

- Information

You must be completely honest about the financial challenges present and future. Be transparent about the issues being faced and the cash position of the institution – ensuring that sufficient funds to meet the institution’s payroll, benefits and other key obligations are able to be met. And you should create a cash flow model that all trustees will understand, regardless of their financial acumen.

As leaders, you must be prepared to address the question “How much longer do we have?” It is this question that keeps many chief executives and CFOs up at night as they consider their options. We are all aware of these sleepless nights, although in the morning you will need to be prepared to make hard decisions and ensure the institution continues to move forward. Once your Board is fully aware of the challenges being faced, start working with your other key financial partners, such as your bank. Make sure that you understand your banking and debt covenants and explore the possibility of extending your line of credit – specifically for the burn months in your cashflow model.

Liquidity matters and your ability to navigate your institution’s cashflow model will help ensure that you have a viable plan to confront your most significant problem – to survive and thrive, to merge, or to close in an orderly manner.

To learn more about SPH Consulting Group and how we can help your organization, contact office@sphconsultinggroup.com.

Writer: Joseph L. Chillo, LP.D, Senior Consultant, SPH Consulting Group

© SPH Consulting Group 2024

Student-athletes are often a microcosm of the overall student body of an institution. The student-athletes of an institution are students just like all others there to get an education, but they also represent the institution in most public arenas and are often at the forefront of the institution. But when an institution is merging with another or even closing, many of the student-athletes are treated the same as every other student, even though they have additional needs that must be considered.

When an institution decides to close, they should create teach-out plans either at the same institution or with another institution to make sure their students have a home to finish their degree without any delays. While this is important to student-athletes as well, a student-athlete must consider more than just the completion of their degree but also the completion of their playing career, if they so choose. Student-athletes choose an institution for reasons of academics but also because of the coach or coaches who recruited them, the teammates they knew already were on the team, and a myriad of other reasons not completely related to the academic program in which they are enrolled.

When an institution is closing, the student-athlete cannot necessarily just go to another school and join a team but must find the right fit for the person and position they occupy on the team. A baseball or softball player who plays catcher cannot just choose any new institution and team but has to consider their remaining eligibility as well as opportunities for playing time at the new institution. If the team has a better catcher, the player has to decide to try to earn playing time or find a different opportunity. All of this takes time. More time than simply transferring to a new academic program, which is why when closures are abrupt and immediate, the student-athlete suffers the most.

When considering mergers, there are differences in the considerations of the general student body and the student-athlete population. Reducing two bursar’s offices or business schools into one is different from the same consideration for athletic departments. With a single institution, one bursar’s office or one school of business is all that is needed and can handle as many students as needed. If more than one athletic department exists within merging institutions, a decision must be made whether to maintain or reduce the number. Unlike the school of business’s ability to handle as many students as there are faculty and classroom spots, each athletic department has a limited number of roster spots per team as well as a limited number of teams. If the decision is to keep all departments, then people continue on with business as usual. If the decision is to eliminate a department or even a team, then the same considerations exist for student-athletes as in a closure, as the number of roster spots are reduced.

Overall, mergers and closures in higher education are occurring more frequently. Each transaction must consider the impact on students. Student-athletes should not be overlooked in the process and should be given the best opportunity to be successful, not just in academics, but in their playing career as well.

To learn more about SPH Consulting Group and how we can help your organization, contact office@sphconsultinggroup.com.

Writer: James Hagler, Consultant, SPH Consulting Group.

© SPH Consulting Group 2024

Mergers are transitional and the transformation requires strong leadership throughout the institution. While it is clear that the Chief Financial or Business Officer must consolidate budgets and other financial instruments and the Chief Academic Officer/Provost must consolidate academic areas, there are some who overlook the critical role that student affairs should assume during a merger. As we noted in our book ‘Strategic Mergers in Higher Education’, a successful merger must include “a compelling unifying vision” and student affairs must play a substantial role in supporting that vision.

The ultimate role of a merger is to create one unified university with each campus having complimentary resources, even though there will be differences based on campus needs. Each campus may have student affairs staff already in place, and most will have established traditions and student resources on each campus including new student orientation, academic resources, and community-building opportunities. Each campus must be equally important just as each student must be equally important; yet, campuses, like students, may have differing needs. Of course, the lead student affairs officer must diligently coordinate student success initiatives across all campuses, preferably in collaboration with other campus divisions.

During the merging process, it is not unusual for one campus to learn that other campuses have successful initiatives that have enhanced student persistence and success on their own campus. The off-campus programming on one campus may be lacking on another. One campus may have had tremendous success with supplemental instruction while another may not offer it at all. Conduct codes, leadership opportunities, health center availability, community building, service learning, and information on student employment should be appropriately provided across the campuses. However, as colleges and universities’ primary mission is to educate and train students, it is not hard to grasp the concept that student affairs should play a significant role in creating a successful merger.

Campus culture plays a significant role in student persistence and success and, therefore, graduation rates. The initiation of a merger can provide opportunities to determine whether the culture on each campus is healthy and, regardless of the strength of the campus culture, what initiatives might enhance student success. Normed surveys can also identify the perception of the campus culture by groups of students. Transfer students, new-from-high-school students, and graduate students may have had different experiences and developed different perceptions.

On one campus where I once worked, I gathered data on the giving rate of recently graduated students who entered as freshmen versus those who entered as transfers. I was surprised to learn that the transfer students had a higher giving rate. Further analysis indicated that, because that campus had a large transfer population, it had developed a robust transfer orientation program, a transfer center, “transfer talkbacks,” and specific events celebrating transfers. While mergers, like other transitions, can be demanding and stressful, they can also provide an opportunity to discover new opportunities and initiatives that, in the end, lead to increased graduation and alumni engagement rates.

Although we should recognize the critical role that student affairs plays in ensuring a successful merger, it is clear that no campus leader works in a vacuum and that collaborative efforts are imperative. Likewise, student affairs leadership must not only be included during the merger or acquisition process, they also must be heavily collaborative. After all, they have much expertise to contribute toward enhancing student success and graduation rates. Because, after all, mergers are primarily about enhancing student experience, access, and success.

To learn more about SPH Consulting Group and how we can help your organization, contact office@sphconsultinggroup.com.

Writer: Bonita C. Jacobs, Senior Consultant, SPH Consulting Group

Our institution is a four-year residential institution that merged with a primarily two-year non-residential institution. Both institutions were successful and performing well. The two-year institution had a satellite campus, and we jointly opened a two-plus-two campus. The institutions have been consolidated for a decade and, looking back, there were some critical issues we had to diligently address. Was it difficult? Of course, change is hard, but we learned a lot through the process. Some of the lessons learned are obvious but often overlooked.

Constituents will be concerned and may feel a sense of loss. The need for frequent and open communication is paramount. Transparency is a must. Our consolidation committee, composed of representatives from each campus, included members of the faculty senate, the staff council, the alumni association, the student government, and the corps advisory council. We held virtual townhall meetings frequently. Participants were able to send questions and each question was answered thoroughly by the president or a vice president. Committee members were also on each campus periodically for question-and-answer forums. We spoke with faculty senate, staff council, and student government.

Students need to be included in the process. Our student governments across our campuses created a plan that consolidated the Student Government Association on each campus into one. The officers for the combined Student Government Association were selected from all campuses; thus, the serving president might be from one campus for a year and from a different campus the next year.

Having outside consultants matters and is necessary in most cases. Not only do they offer guidance, but they can add a stamp of approval beyond the internal process. They can also introduce new ideas and information that the internal committee has not yet considered. We brought in a communications consultant who advised the consolidation committee on a new name, a logo design, and other communication considerations.

Alumni may struggle with the changes, particularly if they are proud of their university and the name it once held.What we learned was that, even though a name change is difficult, the new name can be robust and meaningful. Many of our alumni have asked for an additional diploma bearing our new name.

Remember to keep trustees/board member apprised of every step. You will need their support and guidance, as well as their concerns.

The number of new mergers is increasing, and more are predicted to follow. Merging may seem like a daunting task; however, the result can produce a stronger institution for each campus. It is imperative to rely upon guidance from those who have extensive knowledge about why mergers succeed and why they fail.

To learn more about SPH Consulting Group and how we can help your organization, contact office@sphconsultinggroup.com.

Writer: Bonita C. Jacobs, Senior Consultant, SPH Consulting Group

Recently, Lee Gardner wrote a nice piece entitled ‘When It Comes to College Closures, the Sky Is Never Going to Fall’, where he noted that he has become tired of the decade-long prediction that we would see a wave of college closures. He notes that “the shakeout didn’t come. And at this point, I don’t expect it this year, or next year. Or ever, maybe”. I do feel bad for him, as there are few things worse than unrequited expectations.

But I do think he is looking at the data with a somewhat biased perspective. For starters, what is a wave anyway? And what is its shape? Let us look at the data to understand that question.

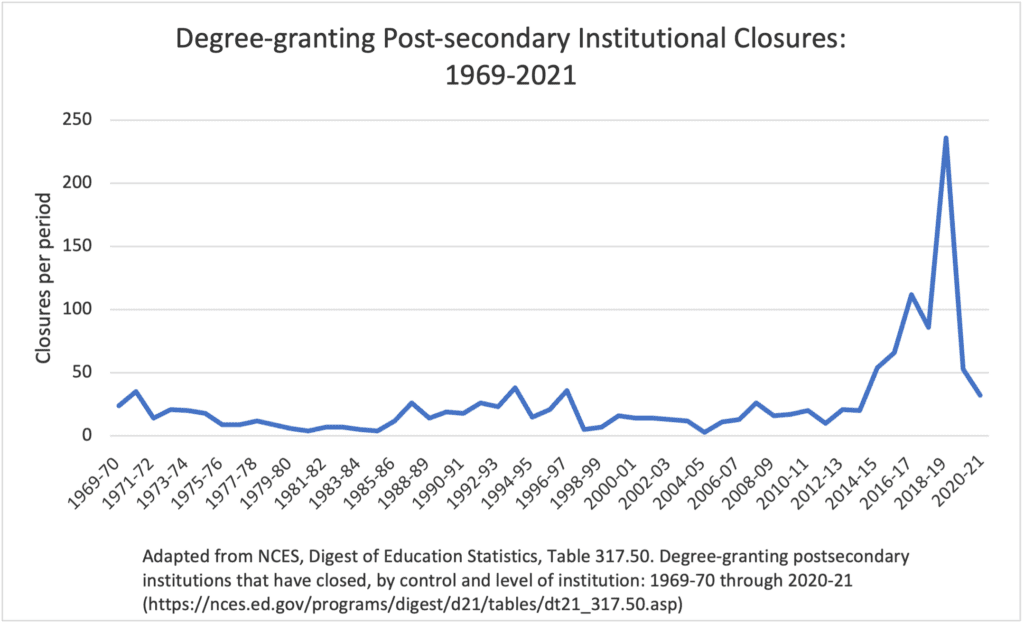

NCES data has noted that between 1969 and 2009 there were 619 closures; in the eleven years between 2010 and 2021 there have been 710 closures. Overall, about 15% of all degree-granting institutions in the U.S. have closed in the past decade or so. A number greater than that of all school closures in the prior 40 years. While this may not be the tsunami that Lee expected it is a ‘wave’ (see graph).

And a wave that has been felt by a growing number of students. The recent analysis by the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (NSCRC), in collaboration with the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (SHEEO), reported on 467 institutions that closed between July 1, 2004, and June 30, 2020. Closures that impacted 143,215 students. An enormous number of individuals affected. Students that were more often of color or disadvantaged. And worse, two-thirds of the students whose colleges closed experienced an abrupt and unplanned closure which detrimentally affected the students’ chances of reenrollment. In fact, almost 90% of the students in the study who did not earn a credential and did not reenroll had experienced an abrupt institutional closure.

It is possible that some of the school closures reported by NCES may have been recorded as ‘closed’ if they had merged with another institution. Unfortunately, our own research indicates that the number of closures far outweighs that of mergers, in a ratio that approximates 7:1. While not all schools can, or should be saved, many of them could have found that a merger with another institution was a good strategic solution – for the preservation of their heritage and their mission, and most importantly, for the benefit of their students.

Unfortunately, most schools, as Lee indicates, “may look for partnerships, mergers, and buyers, although sometimes when it’s far too late.” Waiting too long to search for an institutional partner often results in schools without much left in the way of financial, enrollment, or brand equity. While other institutions, including sister schools, may be willing to assist the failing colleges’ students, through teach-outs, transfer agreements, and the like, few will be willing to, or should, risk their own financial health in the venture.

One of the important points that Lee makes is that institutional leaders, boards and chief executives, will do whatever it takes to keep their institution independent… And the result can be what we have termed ‘Zombie Colleges’. Schools that have progressively declining enrollment and finances, with limited operating cash reserves, often with only enough finances to get them to the end of the academic year – if they are careful – but without the resources needed to mount an effective counter-offensive. In a preliminary analysis, we identified at least 200 Title IV institutions that currently fit the definition. And which will remain so until a catastrophic event, such as a ransomware attack or significant drop in enrollment, spells their end.

So, while we may not (yet) have seen the tsunami that Lee was expecting, there clearly is a wave of closures. And more will continue, as higher education faces excess capacity and a collective loss of 2.0 million students since 2011. A number equivalent to the entire enrollment of almost one-half the schools with less than 5000 students.

So what to do? Colleges and universities should begin to systematically perform 5-year financial planning (yes, you can model most future elements, even the unexpected), begin to consider strategic partnerships, including mergers and acquisitions early, … and never let hope be the guiding plan.

To learn more about SPH Consulting Group and how we can help your organization, contact office@sphconsultinggroup.com.

Writer: Ricardo Azziz, Principal, SPH Consulting Group.

[1] Of closures since 1969, 4.1% were public and 95.9% were private. Of closures of private institutions since 1990 (when private colleges were classified into non-profits and for-profits), 75.1% of closures have been in the for-profit sector.

Higher education has been going through significant change. After years of steady and, at times, substantial growth in demand, the last twelve years have seen a clear significant change in direction. Between 2011 and 2020, institutions of higher education experienced a 10% decline in the demand for the “product” they offer, the once coveted college degree. The reasons for the decline have been studied extensively and range from, the obvious issues of escalating cost, an aging population with a shrinking college age demographic, to a new recognition of the need for people in the various trade industries that do not require a college degree. Models for learning have also changed. Post-Covid that trend has only continued, with the idea of delivering education through distance or remote online learning gaining strength.

Put another way, higher education has lost more than 2 million students annually. This decline in enrollment has led to something virtually unthinkable prior to 2010; old and respected colleges and universities are being forced to close. However, if you look closer at the data, you also see that not all schools are experiencing a decline in enrollment. Larger schools have actually seen an increase in their overall enrollment. For example, if we examine the 20 largest institutions in the U.S. (by enrollment) we observe that between the same years, student enrollment increased by 8%, and was even greater when considering four year institutions only (+10%) or private institutions only (+22%). So, what does all this mean for colleges and universities who are trying to strategically plan for their future and how do they remain “market relevant” in the evolving environment?

Is there a way for smaller colleges and universities to retain their legacy and continue delivering on their underlying mission? The answers are not easy. Not because there are no options, but because the options are often outside the normal “comfort zone” not only for school boards and executives, but also for the extended campus community.

Unlike other sectors of our society, prior to 2010 the world of higher education functioned in its own unique space. Sometimes referred to as the “Ivory Tower,” these organizations functioned with their own rules of engagement, thinking of themselves as different and unique enterprises, where many of the typical rules that govern business did not apply. It was a place for free-thinking people to go, explore through research and teaching with the mission of providing the world its next generation of leaders across all industries. Following World War II, demand was such that there was little reason to be overly concerned about the economic realities of operating the higher education business.

The demand was there, growth was required, and on a relative basis all institutions could increase in size and charge what they needed to charge, and there would be a customer or client who valued their brand and was willing to pay for the product. Post college, the market was demanding that the workforce obtain a college degree in order to secure the best paying jobs and have the greatest opportunity for a better financial future. Unlike other industries, higher education was far less affected by supply and demand, business and economic cycles, changes in the regulatory environment, and even the evolution of technology. In fact, if anything, the rapid evolution of information technology (IT) helped to spur the further demand for trained personnel, which in turn helped colleges and universities as the training ground for this new generation of engineers, scientists, and IT personnel.

Unlike higher education, other industries were unable to escape the reality of a changing and evolving environment. New for more sophisticated technology, the increasing cost of materials, a changing demand for services, increasing regulatory burden, and much more – all impacting virtually every industry from healthcare to transportation to communications to banking and finance. These other industries learned that the market demanded they reconsider how they operate and be open to modifying how they view themselves and retain their relevance. The need to look ahead, strategically plan, flex their size, adjust their operations, and view new partnerships and relationships, all became the basic tools for how they operate.

However, the uninhibited use of these fundamental operating and financial tools and principles have been frequently absent from most institutions of higher education. Many traditional institutes of higher education, in particular private institutions, have functioned primarily as standalone entities, without significant operational or financial ties with others. They have therefore found themselves competing for the same market, expending funds to build similar programs and facilities, and supporting what often is duplicative infrastructure. There has been a general reluctance to explore the development of creative strategic partnerships and relationships.

Included in the idea of considering strategic relationships is a willingness to consider and, as needed, embrace the idea of merging with and/or merging into other compatible organizations. If it is to be used in a meaningful way, consideration of strategic partnerships requires an openness to letting go of some control and accepting that real change is going to be difficult and likely will take the organization and its leaders out of their usual comfort zones. It also means that traditional ways of looking at challenges and how they might be truly mitigated need to be on the table.

Consideration of strategic partnerships requires setting aside egos and a higher degree of transparency then the culture of the organization may be accustomed to. This is perhaps the greatest challenge to considering strategic partnerships in higher education. The willingness of most senior leaders to relinquish some degree of control and accept appropriate risks to their own positions. These concepts are not new to other industries, and it is in fact how organizations in health care, communications, and the like have managed to evolve and remain successful.

Ultimately, it all comes down to leadership answering the question, “What is more important?” Is it retaining our name, traditions, and independence just because this is how we have always operated? Or can we see ourselves in a new way, relinquishing some degree of control and finding new ways of being, in order to preserve our legacy and, even more importantly, create new legacies that meet the realities of today’s marketplace?

To learn more about SPH Consulting Group and how we can help your organization, contact office@sphconsultinggroup.com.

Writer: Richard Katzman, Senior Consultant, SPH Consulting Group.

As we navigate the increasingly choppy waters of higher education, we must remember a key fundamental – stories are how we communicate around complexity. Stories have been central to human communication for thousands of years. From 30,000-year-old cave paintings in France, to the blockbuster opening of Top Gun: Maverick last summer, we are clearly drawn to a good story.

Why is the narrative form so powerful and so popular? I believe it is due to two key features: the way stories engage our senses and the work that stories do for us.

Stories engage more areas of our brain as we read or listen to them. Unlike “info dumps” in endless PowerPoint slide decks, good stories use language to help us see, hear, feel, and taste things from another place and time. They draw on our sense memories to stir our emotions.

Because they so fully engage us, stories can be powerful. They influence who we think we are, how we are connected to others, and they motivate us to do what we do and believe what we believe.

Our institutions are fundamentally shaped by the stories we tell about our origins, our history, and our work together. They are the most powerful creators and sustainers of our organization’s identity and culture.

Do you know what your organization’s most important stories are? Do you know who is telling your stories?

As you consider changes to your organization, such as a new name, new brand campaign, a merger or a significant evolution in mission and vision, have you considered how those changes will impact the story your organization shares about itself? Will the changes be a new chapter or a total re-write of your story?

Have you, also, considered how your stories can help manage the change you are planning, leveraging your culture to make your change successful?

As you think through these questions, here are some storytelling principles to keep in mind:

- The leader of an organization should be its “storyteller-in-chief”. An organization’s stories should be incorporated into leadership communication strategies.

- Your story should have a “plot” that is consistent with your mission, vision, and values. The plot is what moves the story forward. Your mission, vision, and values should provide the energy and motivation that propels your organization forward to overcome challenges.

- Every good story has a protagonist. Your people should be the heroes of your story.

- Every good story has an obstacle created by an antagonist. Be sure to identify who or what is standing between your organization and its people and success, and how those challenges were or will be overcome.

- Good stories make sense to people—there is a logic to them. Think about the movie or television show that flops because it is incoherent, too far-fetched or because the characters do not behave in the way we would behave if we were in their shoes. Make sure your story is credible, that it is internally consistent and that it makes sense with what we generally know about human behavior.

- Stories that last the test of time and serve as the bedrocks of an organization’s culture shape the way new facts and stories are evaluated. As a result, change must account for an institution’s past.

- Language is powerful. The difference between someone who merely provides information, and a good storyteller is that the storyteller uses language to engage the senses and call upon the values of their constituents. The right language can make a story much more powerful.

As you begin to consider major opportunities for your institution, such as a merger, acquisition, consolidation, or even closure, let SPH Consulting Group help you craft and communicate that story. A story that will help you and your organization achieve its goals and vision.

To learn more about SPH Consulting Group and how we can help your organization, contact office@sphconsultinggroup.com.

Writer: Karla Leeper, Senior Consultant, SPH Consulting Group.

We hear much regarding the crises facing higher education today – tumbling enrollments, changing student demographics, increasing institutional costs, the even greater increase in costs to students and the exponential rise in student debt, the challenges occasioned by increasingly influential rankings, the declining interest in the humanities and liberal arts, the rise in market-capturing online programming, and much more. And we hear much about the suffering of the small, mostly private, mostly stand-alone institution. But what we do not hear enough about is the important opportunities present – on both sides of the negotiation table.

What the current environment has begun to achieve, albeit slowly, is to encourage college and university executives and governing boards to begin to think beyond the usual strategies of enrollment management, enhanced campus amenities, tuition and fee discounting, and expanded online programming and adult learning. More and more executives and board members are beginning to consider how a strategic partnership, possibly including a merger (sometimes termed consolidation or acquisition depending on perspective), may be the best tactic to achieve growth, sustainability, and success – for both the institution and students.

Why should institutional leaders consider a merger now? Because, paraphrasing Churchill, “Never let a good crisis go to waste”. As the pressures on many institutions rise, the opportunities also increase.

For example, some colleges or universities may want to expand their geographic or market footprint by partnering or merging with an institution that is already located in the area or community of interest.

Or some schools may want to develop programs in law, health sciences, or manufacturing. What better way to do so rapidly than to merge with a school that is already offering such programs? Especially, considering the many specialized schools throughout the nation.

Or some institutions may want to expand their degree portfolio, adding bachelors, masters, or doctorates, by merging with a school that already offers these degrees. Or, alternatively, a school may want to gain a secure base of undergraduates. What better way to do so than merging with a two-year college?

And still other institutions may seek future sustainability, ensuring that their mission is continued and students are served, albeit perhaps in a modified manner.

Yes, it is a time of opportunity. But a few things should be kept in mind.

First, institutions should not wait too long, particularly if they are seeking greater sustainability. Opportunities should be explored, deliberately and with resolve, when the institutions are still in good financial and political state.

Second, institutions should be strategic. While opportunism is often the leading guide to strategic partnerships, we believe that is best for institutional leaders to have clarity around the strategic tactics that are most fitting to their institutions. And which should guide their search for a strategic partner.

Third, institutional leaders should remember to put their ego in their pocket. These partnerships are not about them. They are about the school and its future. And most importantly, they are about the students. So, when in doubt, ask what would be best for the students? Today and in the future?

So, are you and your institution making the most of this time of opportunity?

To learn more about SPH Consulting Group and how we can help your organization, contact office@sphconsultinggroup.com.

Writer: Ricardo Azziz, Principal, SPH Consulting Group.

© SPH Consulting Group 2023

It’s about the right expertise, experience, objectivity, perspective, time, focus, communication, and education.

When all of us begin to deal with areas that we are unfamiliar with, we often turn for advice and guidance to those who have more experience and expertise in the field. And so it is when a merger, acquisition or consolidation is being considered. Or even earlier in the process, when potential options to expand programming or grow enrollment rapidly want to be explored. Or even more commonly, when strategies and tactics to address a difficult enrollment and financial environment are being pursued.

Expertise is the principal reason leaders of higher education think of when considering an external consultant. And it is true that many consultants bring to the table expertise. Expertise that is relatively infrequent.

But do they bring experience? Because the one thing I have learned as someone who actually led two different consolidations, is that experience counts the most. Experience that is relatively uncommon in higher education. But not all consultants have ‘on-the-ground’ experience. Unique among consultants, all SPH Consulting Group team members have served in leadership and administrative roles during mergers, acquisitions, or consolidations in higher education. They get it.

While expertise and experience may be the reason that a consultant is selected, there are many more reasons to hire an outside consultant when considering these major corporate transformations in higher education.

For starters, seeking outside counsel from an expert and experienced firm will provide needed objectivity and perspective. Impartiality and a different perspective that is often in short supply when transformational options as emotionally charged as a merger is being considered. Consultants can provide external analysis and due diligence that is critically needed when making these types of decisions. Information that will help validate any decision that is made – whether to proceed or not with the proposed transformation. And dispassionate external validation to a decision provides the added benefit to institutional leaders of what we euphemistically call ‘air cover’ – protection for leaders that would not exist if they had chosen to make these decisions alone.

In addition, hiring the right consultant allows the appropriate amount of time and focus to be given to considering the pros and cons of the option. Leaders in higher education are busy individuals. In fact, in an analysis of some 40 mergers occurring since 2000, it was indicated that “successful” mergers seem to involve the decision-makers who were managing their institutions well. All leaders, regardless of how experienced or outstanding they may be, have limited bandwidth and attention spans. And, good decision-making and analysis around major institutional restructuring require significant time and attention. Time and attention that leaders cannot afford if they are to manage their institutions well, while also arriving at the best and most informed decision. The right consultant will serve to ‘extend’ the leaders’ time and focus, providing careful analysis and due diligence for ready consideration and decision-making.

Finally, the right and experienced consultant will be able to assist in communicating and educating important stakeholders including boards, executive leaders, and key community members concerning the environmental challenges, the potential options, the process forward, and much more. While these individuals may not always listen to their own, they almost always listen to national experts. Experts that SPH Consulting Group has in abundance.

When a merger, acquisition, consolidation, corporate conversion, or other major institutional restructuring is being considered, hiring the right consultant should be able to provide the right expertise, experience, objectivity, perspective, time, focus, communication, and education. Critical benefits, when major and uncommon options need to be considered and decisions made in a timely manner.

To learn more about SPH Consulting Group and how we can help your organization, contact office@sphconsultinggroup.com.

Writer: Ricardo Azziz, Principal, SPH Consulting Group.

© SPH Consulting Group 2023

When higher education institutions merge (consolidate) to create a new institution, most academic and other departments are combined to reduce duplication of positions and services. This helps reduce the number of administrative positions and creates economies of scale which helps reduce operating costs. But what becomes of athletic departments in a merger?

There are generally three options for athletics when multiple higher education institutions consolidate into a single institution. The easiest to manage can be seen in the consolidation Middle Georgia College and Macon State College that resulted in what is today Middle Georgia State University, in which only one of the institution had athletics department. In this case, the single athletic department is continued.

The second option was seen in the consolidation of Georgia Southern University, which was a member of NCAA Division I, with Armstrong State University, which was a member of NCAA Division II. In this case, the choice was to discontinue Armstrong’s athletics (in what ended up being the Savannah campus of Georgia Southern University) and the Division I program was continued on the Statesboro (main) campus of Georgia Southern University. In this case, the decision appears to have been based on which division the merged school chose to continue and invest in. But even in the example provided, a number of questions remain. What happens with students interested in athletics who are on the Savannah campus of the merged entity? In the Georgia Southern University example, one institution was dissolved while the other remained in operation. But what happens if two institutions have operating athletic programs and both institutions are dissolved in favor of a new consolidated institution? These are complex questions that require careful analysis and lead to the third possibility.

A third option that may be considered when each of the merging institutions have an existing athletic program, is to keep both athletic departments open and run as separate departments on different campuses. Whether the departments are in the same association (NCAA, NAIA, etc.) or not, maintaining two athletic departments is an option that often needs to be considered. The mergers in the University System of Pennsylvania are an example in which six different institutions were merged into two (three in each case) yet each retained a separate athletic department on each campus, and compete against each other.

Maintaining separate athletic departments can become a necessity for enrollment. Mergers are designed to help the school become stronger and losing a percentage of student-athletes due to combining athletic departments can have a negative impact. At smaller, private institutions, student-athlete enrollment can comprise as much as 60%, if not more, of the overall student-body and adding new athletic teams or club sports for increasing enrollment. If two institutions are merged in order to increase the sustainability of both, losing any portion of the student population due to the loss of an athletic program needs to be balanced against overall costs of that program, financially and politically.

Considering which program to continue and which to discontinue will depend on many factors including the extent to which enrollment, branding, and fundraising depend on athletics, the costs of the program, Title IX and equity considerations, future potential, athletic association, conference, and much more. Determining how to manage these questions is a key component in the process of merging institutions of higher education.

To learn more about SPH Consulting Group and how we can help your organization, contact office@sphconsultinggroup.com.

Writer: James Hagler, Consultant, SPH Consulting Group.

© SPH Consulting Group 2023

Higher education is a service and institutions of higher education are wise to consider themselves service providers. Most do not frame academia in this way, but just as an auto repair shop fixes a car or a health care provider gets a patient back on his feet, colleges and universities serve students through teaching, research and community service. In services, we know consumers are risk-averse. It is simple human nature. People want to find a way to engage with a service provider to have their expectations met and to do so with limited interruption or friction. A merger or consolidation in higher education could easily be a source of friction or discomfort to consumers including students, faculty, staff, alumni, and communities served. So how do we approach our stakeholder engagement to minimize the risks and prepare our communities for change? At SPH Consulting Group, we consider the following when preparing our clients for success.

Determining your audiences.

When colleges or universities make the decision to merge or consolidate, there are numerous parties with a vested interest in the outcome of such a decision: alumni, current and prospective students, donors, faculty, staff, affiliates, regional accreditors, state office of education, and many more. Consider all who may be impacted or have even a peripheral interest in what is happening, including peers. And especially if you are a state-funded institution, you must ensure state and local officials are also included.

Segmenting your audiences.

As with any organizational change, providing context is key. Everyone will want to know the answer to the question, “What is in it for me?” The answer to this question will differ for each audience. However, it is key to segment your audiences, to communicate the right message, at the right time, and to the right people.

Creating a systematic approach for all voices to be heard – and promptly answered.

Often times in academia, we find the noisiest constituencies or the loudest voices are often responded to first. This leads to disengagement from other key stakeholders who don’t know how or when to voice their opinions. Or simply are trying to voice their thoughts in a quieter, calmer, more less confrontational manner. To prevent disengagement or lopsided feedback, administrations should take a proactive approach and a priori determine primary and secondary audiences. Then allow individuals to express themselves in a documented fashion, whether through an online survey or multiple town halls. Consider the timing of events to ensure audience availability and participation. Ensure the questions you are asking are related to the segment of the audience you are addressing. And consider the following – Do they have enough information to answer the questions? How will their feedback influence future decisions?

As with any organization in the service industry, if institutions put PEOPLE FIRST in their stakeholder engagement planning, the outcome will be sustainable and will create loyalty to the institution’s brand, post-merger.

Writer: Aubrey Hinkson, Consultant, SPH Consulting Group

To learn more about SPH Consulting Group and how we can help your organization, contact office@sphconsultinggroup.com.